Chapter VI • The Foreign Policy of the Truman Administration

For many of President Truman’s early mistakes in foreign policy, he cannot rightly be blamed. As a Senator he had specialized

in domestic problems and was not at any time a member of the Foreign Relations Committee. Nor had he by travel scholarship

built up a knowledge of world affairs. Elevated to second place on the National Democratic ticket by a compromise and hated

by the pro-Wallace leftists around Franklin Roosevelt, he was snubbed after his election to the Vice-Presidency in 1944

and was wholly ignorant of the tangled web of our relations with foreign countries when he succeeded to the Presidency on April

12, 1945 — midway between the Yalta and Potsdam conferences.

Not only was Mr. Truman inexperienced in the field of foreign affairs; it has since been authoritatively stated that much vital

information was withheld from him by the hold-over Presidential and State Department cabals. This is not surprising in

view of the deceased President’s testimony to his son Elliott on his difficulty (Chapter V) in getting the truth from

“the men in the State Department, those career diplomats.” Significantly, the new President was not allowed to know of

his predecessors reputed despair at learning that his wisecracks and blandishing smiles had not induced Stalin to renounce

the tenets of bloody and self-aggrandizing dialectic materialism, a state-religion of which he was philosopher, pontiff,

and commander-in-chief.

President Truman brought the war to a quick close. His early changes in the cabinet were on the whole encouraging.

The nation appreciated the inherited difficulties under which the genial Missourian labored and felt for him a nearly unanimous

good will.

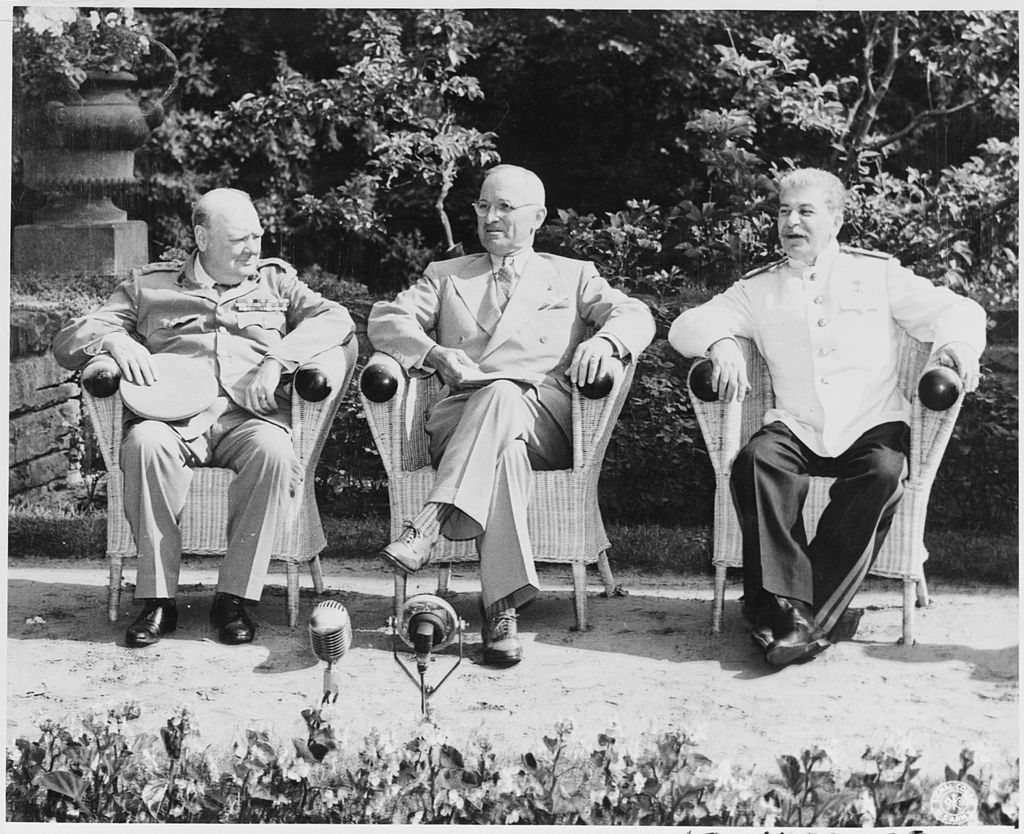

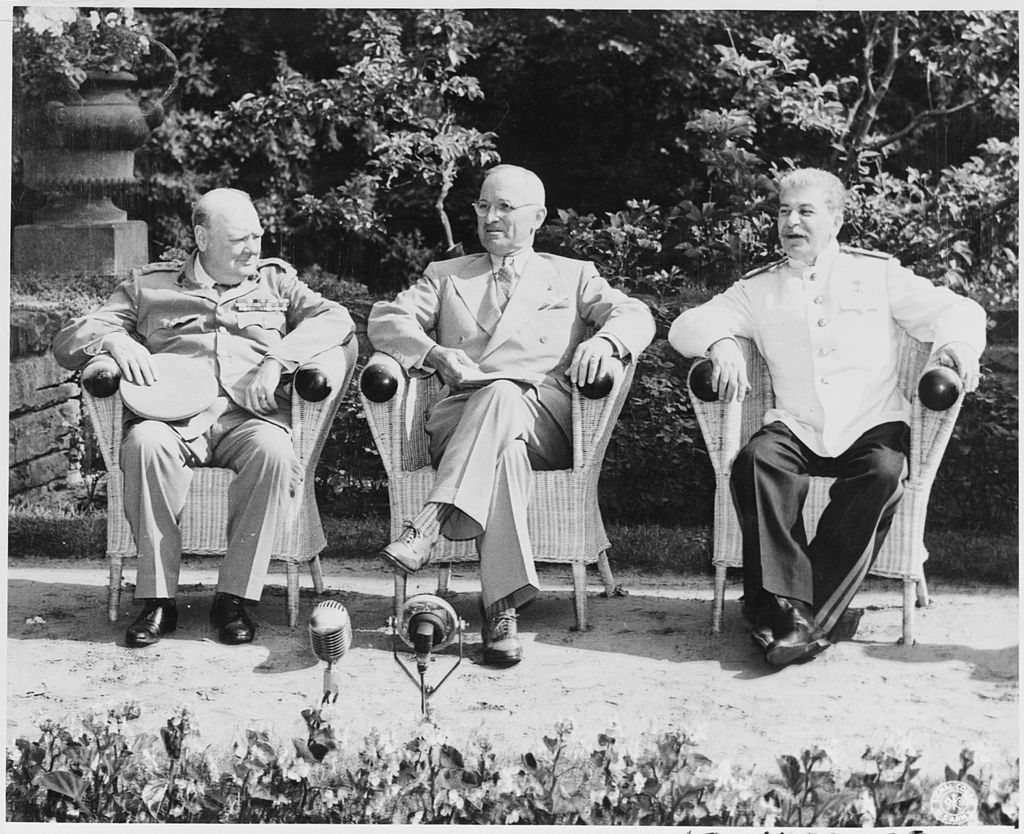

In the disastrous Potsdam Conference decisions (July 17-August 2, 1945), however, it was evident (Chapter IV) that anti-American

brains were busy in our top echelon. Our subsequent course was equally ruinous. Before making a treaty of peace, we

demobilized — probably as a part of the successful Democratic-leftist political deal of 1944 — in such a way as to reduce

our armed forces quickly to ineffectiveness. Moreover, as one of the greatest financial blunders in our history, we gave away,

destroyed, abandoned, or sold for a few cents on the dollar not merely the no longer useful portion of our war materiel but many

items such as trucks and precision instruments which we later bought back at market value! These things were done in spite

of the fact that the Soviet government, hostile to us by its philosophy from its inception, and openly hostile to us after

the Tehran conference, was keeping its armed might virtually intact.

Unfortunately, our throwing away of our military potential was but one manifestation of the ineptitude or disloyalty which

shaped our foreign policy. Despite Soviet hostility, which was not only a matter of old record in Stalin’s public utterances,

but was shown immediately in the newly launched United Nations, we persisted in a policy favorable to world domination by the

Moscow hierarchy. Among the more notorious of our pro-Soviet techniques was our suggesting that “liberated” and other nations

which wanted our help should be ruled by a coalition government including leftist elements. This State Department scheme tossed

one Eastern European country after another into the Soviet maw, including finally Czechoslovakia. This foul doctrine of the left

coalition and its well-known results of infiltrating Communists into key positions in the governments of Eastern Europe

will not be discussed here, since the damage is one beyond repair as far as any possible immediate American action

is concerned. Discussion here is limited to our fastening of the Soviet clamp upon the Eastern Hemisphere in three areas

still the subject of controversy. These are (a) China, (b) Palestine, and (e) Germany. The chapter will be

concluded by some observations (d) on the war in Korea.

The Truman policy on China can be understood only as the end-product of nearly twenty years of American-Chinese relations.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt felt a deep attachment to the Chiangs and deep sympathy for Nationalist Chins — feelings

expressed as late as early December, 1943, shortly after the Cairo Declaration (November 26, 1943), by which Manchuria was

to be “restored” to China, and just before the President suffered the mental illness from which he never recovered.

It was largely this friendship and sympathy which had prompted our violent partisanship for China in the Sino-Japanese

difficulties of the 1930′s and early 1940′s. More significant, however, than our freezing of Japanese assets in the

United States, our permitting American aviators to enlist in the Chinese army, our gold and our supplies sent in by air,

by sea, and by the Burma road, was our ceaseless diplomatic barrage against Japan in her role as China’s enemy (see

United States Relations With China With Special Reference to the Period 1944-1949, Department of State, 1949, p. 25 and passim).

When the violent phase of our already initiated political war against Japan began with the Pearl Harbor attack of December 7, 1941,

we relied on China as an ally and as a base for our defeat of the island Empire. On March 6, 1942, Lieutenant

General Joseph W. Stilwell “reported to Generalissimo Chiang” (op. cit., p. xxxix). General Stilwell was not only

“Commanding General of United States Forces in the China-Burma-India Theater” but was supposed to command “such

Chinese troops as Generalissimo Chiang Kai-Shek might assign him” (op. cit., p.30) and in other ways consolidate

and direct the Allied war effort. Unfortunately, General Stilwell had formed many of his ideas on China amid a

coterie of leftists led by Agnes Smedley as far back as 1938 when he, still a colonel, was a U.S. military attache in Hankow,

China (see The China Story, by Freda Utley, Henry Regnery Company, Chicago, 1951, $3.50). It is thus not surprising that

General Stilwell quickly conceived a violent personal animosity for the anti-Communist Chiang

(Saturday Evening Post, January 7, 14, 21, 1950). This personal feeling, so strong that it results in amazing vituperative poetry

(some of it reprinted in the post), not only hampered the Allied war effort but was an entering wedge for vicious anti-Chiang

and pro-Communist activity which was destined to change completely our attitude toward Nationalist China.

The pro-Communist machinations of certain high placed members of the Far Eastern Bureau of our State Department and of

their confederates on our diplomatic staff in Chungking (for full details, see The China Story) soon became obvious to

those in a position to observe. Matters were not helped when “in the spring of 1944, President Roosevelt appointed

Vice-President Henry A. Wallace to make a trip to China” (United States Relations With China, p. 55). Rebutting what he

considered Mr. Wallace’s pro-Communist attitude, Chiang “launched into a lengthy complaint against the Communists,

whose actions, he said, had an unfavorable effect on Chinese morale … The Generalissimo deplored propaganda to

the effect that they were more communistic than the Russians” (op. cit., p. 56).

Our Ambassador to China, Clarence E. Gauss, obviously disturbed by the Wallace mission and by the pro-Communist attitude

of his diplomatic staff, wrote as follows (op. cit, p. 561) to Secretary Hull on August 31, 1944:

… China should receive the entire support and sympathy of the United States Government on the domestic problem of

Chinese Communists. Very serious consequences for China may result from our attitude. In urging that China resolve differences

with the Communists, our Government’s attitude is serving only to intensify the recalcitrance of the Communists. The request

that China meet Communist demands is equivalent to asking China’s unconditional surrender to a party known to be

under a foreign power’s influence (the Soviet Union).

With conditions in China in the triple impasse of Stilwell-Chiang hostility, American pro-Communist versus Chinese anti-Communist

sentiment and an ambassador at odds with his subordinates, President Roosevelt sent General Patrick J. Hurley to

Chungking as his Special Representative “with the mission of promoting harmonious relations between Generalissimo Chiang

and General Stilwell and of performing certain other duties” (op. cit, p. 57). Ambassador Gauss was soon

recalled and General Hurley was made Ambassador.

General Hurley saw that the Stilwell-Chiang feud could not be resolved, and eventually the recall of General Stilwell

from China was announced. With regard, however, to our pro-Communist State Department representatives in China, Ambassador

Hurley met defeat. On November 26, 1945, he wrote President Truman, who had succeeded to the Presidency in April, a letter

of resignation and gave his reasons:

… The astonishing feature of our foreign policy is the wide discrepancy between our announced policies and our conduct

of international relations, for instance, we began the war with the principles of the Atlantic Charter and democracy as our

goal. Our associates in the war at that time gave eloquent lip service to the principles of democracy. We finished the war

in the Far East furnishing lend-lease supplies and using all our reputation to undermine democracy and bolster imperialism

and Communism …

… it is no secret that the American policy in China did not have the support of all the career men in the State Department …

Our professional diplomats continuously advised the Communists that my efforts in preventing the collapse of the

National Government did not represent the policy of the United States. These same professionals openly advised the

Communist armed party to decline unification of the Chinese Communist Army with the National Army unless the

Chinese Communists were given control …

Throughout this period the chief opposition to the accomplishment of our mission came from the American career diplomats

in the Embassy at Chungking and in the Chinese and Far Eastern Divisions of the State Department.

I requested the relief of the career men who were opposing the American policy in the Chinese Theater of war.

These professional diplomats were returned to Washington State Department as my supervisors. Some of these same career men whom I

relieved have been assigned as advisors to the Supreme Commander in Asia (op. cit, pp. 581-582).

President Truman accepted General Hurley’ s resignation with alacrity. Without a shadow of justification, the able

and patriotic Hurley was smeared with the implication that he was a tired and doddering man, and he was not even allowed

to visit the War Department, of which he was former Secretary, for an interview. This affront to a great American ended

our diplomatic double talk in China. With forthrightness, Mr. Truman made his decision. Our China policy henceforth was to

be definitely pro-Communist. The President expressed his changed policy in a “statement’ made on December 15, 1945.

Although the Soviet was pouring supplies and military instructors into Communist-held areas, Mr. Truman said that the

United States would not offer “military intervention to influence the courses of any Chinese internal strife.”

He urged Chiang’s government to give the Communist “elements a fair and effective representation in the Chinese National Government”.

To such a “broadly representative government” he temptingly hinted that “credits and loans” would be forthcoming

(op. cit, pp. 608-609). President Truman’s amazing desertion of Nationalist China, so friendly to us throughout

the years following the Boxer Rebellion (1900) has been thus summarized (NBC Network, April 13, 1951),

by Congressman Joe Martin:

President Truman, on the advice of Dean Acheson, announced to the world on December 15, 1945, that unless communists were

admitted to the established government of China, aid from America would no longer be forthcoming. At the same time, Mr.

Truman dispatched General Marshall to China with orders to stop the mopping up of communist forces which was being carried

to a successful conclusion by the established government of China.

Our new Ambassador to China General of the Army George C. Marshall, conformed under White House directive (see his testimony

before the Combined Armed Services and Foreign Relations Committees of the Senate, May, 1951) to the dicta of Relations

the State Department’s Communist-inclined camarilla, and made further efforts to force Chiang to admit Communists to his

Government in the “effective” numbers, no doubt, which Mr. Truman had demanded in his “statement’ of December 15.

The great Chinese general, however, would not be bribed by promised “loans” and thus avoided the trap with which our

State Department snared for Communism the states of Eastern Europe. He was accordingly paid off by the mishandling of

supplies already en route, so that guns and ammunition for those guns did not make proper connection as well as by the

eventual complete withdrawal of American support as threatened by Mr. Truman

For a full account of our scandalous pro-Communist moves in denying small arms ammunition to China; our charging China $162.00

for a bazooka (whose list price was $36.50 and “surplus” price to other nations was $3.65) when some arms were sent; and

numerous similar details, see The China Story, already referred to.

Thus President Truman, Ambassador Marshall, and the State Department prepared the way for the fall of China to Soviet control.

They sacrificed Chiang, who represented the Westernized and Christian element in China, and they destroyed a friendly

government, which was potentially our strongest ally in the world — stronger even than the home island of maritime Britain

in this age of air and guided missiles. The smoke-screen excuse for our policy — namely that there was corruption in

Chiang’s government — is beyond question history’s most glaring example of the pot calling the kettle black.

For essential background material, see Shanghai Conspiracy by Major General Charles A. Willoughby, with a preface

by General of the Army Douglas MacArthur(Dutton, 1952).

General Ambassador Marshall became Secretary of State in January, 1947, On July 9, 1947, President Harry S. Truman directed

Lieutenant General Albert C. Wedemeyer, who had served for a time as “Commander-in-Chief of American Forces in the Asian

Theater” after the removal of Stilwell, to “proceed to China without delay for the purpose of making an appraisal of the political,

economic, psychological and military situations — current and projected.” Under the title, “Special Representative of

the President of United States,” General Wedemeyer worked with the eight other members of his mission from July 16 to September

18 and on September 19 transmitted his report (United States Relations with China, pp. 764-814) to appointing authority, the President.

In a section of his Report called “Implications of ‘No Assistance’ to China or Continuation of ‘Wait and See’ Policy,”

General Wedemeyer wrote as follows:

To advise at this time a policy of “no assistance” to China would suggest the withdrawal of the United States Military

and Naval Advisory Groups from China and it would be equivalent to cutting the ground from under the feet of the Chinese

Government. Removal of American assistance, without removal of Soviet assistance, would certainly lay the country open

to eventual Communist domination. It would have repercussions in other parts of Asia, would lower American prestige in

the Far East and would make easier the spread of Soviet influence and Soviet political expansion not only in Asia but in

other parts of the world.

Here is General Wedemeyer’s conclusion as to the strategic importance of Nationalist China to the United States:

Any further spread of Soviet influence and power would be inimical to United States strategic interests.

In time of war the existence of an unfriendly China would result in denying us important air bases for use as

staging areas for bombing attacks as well as important naval bases along the Asiatic coast. Its control by

the Soviet Union or a regime friendly to the Soviet Union would make available for hostile use a number of warm water

ports and air bases. Our own air and naval bases in Japan, Ryukyus and the Philippines would be subject to relatively

short range neutralizing air attacks. Furthermore, industrial and military development of Siberia east of Lake Baikal

would probably make the Manchurian area more or less self-sufficient.

Here are the more significant of the Wedemeyer recommendations:

It is recommended:

That the United States provide as early as practicable moral, advisory and material support to China in order

to prevent Manchuria from becoming a Soviet satellite, to bolster opposition to Communist expansion and to contribute

to the gradual development of stability in China …

That arrangements be made whereby China can purchase military equipment and supplies (particularly motor maintenance parts),

from the United States.

That China be assisted in her efforts to obtain ammunition immediately …

The [sic] military advice and supervision be extended in scope to include field forces training centers

and particularly logistical agencies.

Despite our pro-Communist policy in the previous twenty months, the situation in China was not beyond repair at the time

of the Wedemeyer survey. In September, 1947, the “Chiang government had large forces still under arms and was in control of all

China south of the Yangtze River, of much of North China, with some footholds in Manchuria”

(W. H. Chamberlin, Human Events, July 5, 1950). General Wedemeyer picked 39 Chinese divisions to be American-sponsored and

these were waiting for our supplies and our instructors — in case the Wedemeyer program was accepted.

But General Wedemeyer had reported that which his superiors did not wish to hear. His fate was a discharge from

diplomacy and an exile from the Pentagon. Moreover, the Wedemeyer Report was not released until August, 1949.

Meanwhile, in the intervening two years our pro-Communist policy of withdrawing assistance from Chiang, while the Soviet

rushed supplies to his enemies, had tipped the scales in favor of those enemies, the Chinese Communists.

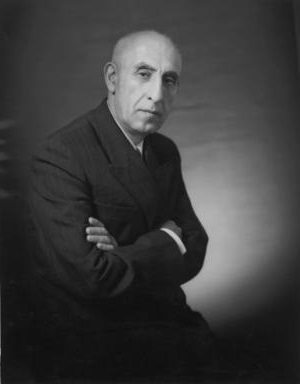

Needless to say, under Mr. Dean Acheson, who succeeded Marshall as Secretary of State (January, 1949), our pro-Soviet policy

in China was not reversed! Chiang had been holding on somehow, but Acheson slapped down his last hope. In fact, our

Secretary of State — possibly by some strange coincidence — pinned on the Nationalist Government of China the

term “reactionary” (August 6, 1949), a term characteristically applied by Soviet stooges to any unapproved person or policy,

and said explicitly that the United States would give the Nationalist Government no further support.

Meanwhile, the Soviet had continued to supply the Chinese Communists with war materiel at a rate competently estimated

at eight to ten times the amount per month we had furnished — at the peak of our aid — to Chiang’s Nationalists. Chiang’s troops,

many of them without ammunition, were thus defeated, as virtually planned by our State Department, whose Far Eastern Bureau

was animated by admirers of the North Chinese Communists. But the defeat of Chiang was not the disgrace his enemies

would have us believe. His evacuation to Formosa and his reorganization of his forces on that strategic island were far

from contemptible achievements. Parenthetically, as our State Department’s wrong-doing comes to light, there

appears a corollary re-evaluation of Chiang. In its issue of April 9, 1951, Life said editorially that “Now we have only

to respect the unique tenacity of Chiang Kai Shek in his long battle against Communism and take full advantage of

whatever the Nationalists can do now to help us in this struggle for Asia.” It should be added here that any idea of

recognizing Communist China as the representative government of China is absurd. According to a Soviet Politburo

report (This Week, September 30, 1951) the membership of the Chinese Communist Party is 5,800,000.

The remainder of China’s 450,000,000 or 475,000,000 people, in so far as they are actually under Communist control, are slaves.

But — back to the chronology of our “policy” in the Far East. On December 23, 1949, the State Department sent to five hundred

American agents abroad (New York Journal-American, June 19, 1951, p. 18) a document entitled “Policy Advisory

Staff, Special Guidance No. 38, Policy Information Paper — Formosa.” As has been stated in many newspapers, the purpose of

this policy memorandum was to prepare the world for the United States plan for yielding Formosa (Taiwan, in Japanese

terminology) to the Chinese Communists. Here are pertinent excerpts from the surrender document which, upon its release in june, 1951,

was published in full in a number of newspapers:

Loss of the island is widely anticipated, and the manner in which civil and military conditions there have deteriorated

under the Nationalists adds weight to the expectation …

Formosa, politically, geographically, and strategically is part of China in no way especially distinguished or important …

Treatment: …All material should be used best to counter the impression that … its [Formosa's] loss would seriously damage the

interests of the United States or of other countries opposing Communism [and that] the United States is responsible

for or committed in any way to act to save Formosa . . .

Formosa has no special military significance . . .

China has never been a sea power and the island is of no special strategic advantage to Chinese armed forces.

This State Department policy paper contains unbelievably crass lies such as the statement that the island of Formosa is,

in comparison with other parts of China “in no way especially distinguished or important” and the claim that the island would

be “of no special strategic advantage” to its Communist conquerors. It contains an unwarranted slam at our allies,

the Chinese Nationalists, and strives to put upon our ally Britain the onus for our slight interest in the island — an

interest the “policy memorandum” was repudiating! It is hard to see how the anonymous writer of such a paper could be regarded

as other than a scoundrel. No wonder the public was kept in ignorance of the paper's existence until the MacArthur

investigation by the Senate raised momentarily the curtain of censorship!

In a “Statement on Formosa” (New York Times, January 6, 1950), President Truman proceeded cautiously on the less explosive

portions of the “Policy Memorandum,” but declared Formosa a part of China — obviously, from the context, the China of

Mao Tse-Tung — and continued: “The United States has no desire to obtain special rights or privileges or to establish military

bases on Formosa at this time. Nor does it have any intention of utilizing its armed forces to interfere in the

present situation.” The President’s statement showed a dangerous arrogation of authority, for the wartime promises

of the dying Roosevelt had not been ratified by the United States Senate, and in any case a part of the Japanese Empire was

not at the personal disposal of an American president. More significantly, the statement showed an indifference to the safety

of America or an amazing ignorance of strategy, for any corporal in the U.S. army with a map before him

could see that Formosa is the virtual keystone of the U.S. position in the Pacific. It was also stated by our

government “a limited number of arms for internal security.”

Six days later (January 12, 1950) in an address at a National Press Club luncheon, Secretary Acheson announced

a “new motivation of United States Foreign policy,” which confirmed the President’s statement a week before, including specifically

the “hands off” policy in Formosa. Acheson also expressed the belief that we need not worry about the Communists in China

since they would naturally grow away from the Soviet on account of the Soviet’s “attaching” North China

territory to the great Moscow-ruled imperium (article by Walter H. Waggoner, New

York Times, January 13, to January 10, 1950).

These sentiments must have appealed to Governor Thomas E. Dewey, of New York, for at Princeton University on April 12,

he called for Republican support of the Truman-Acheson foreign policy and specifically commended the appointment of John Foster

Dulles (for the relations of Dulles with Hiss, see Chapter VIII) as a State Department “consultant.”

Mr. Acheson’s partly concealed and partly visible maneuverings were thus summed up by Walter Winchell

(Dallas Times Herald, April 16, 1951):

These are the facts. Secretary Acheson … is on record as stating we would not veto Red China if she succeeded in getting

a majority vote in the UN … As another step, Secretary Acheson initiated a deliberate program to play down the importance of

Formosa.

Mr. Winchell also mentioned Senator Knowland’s “documentary evidence” that those who made

State Department policy had been instructed by Secretary Acheson to “minimize the strategic importance of Formosa”

All of this was thrown into sharp focus by President Truman when he revealed in a press

conference (May 17, 1951) that his first decision to fire General MacArthur a

year previously had been strengthened when the Commander in Japan protested in

the summer of 1950 that the proposed abandonment of Formosa would weaken the

U.S. position in Japan and the Philippines!

“No matter how hard one tries,” The Freeman summarized on June 4, 1951, “there is no way of

evading the awful truth: The American State Department wanted Marxist Communists

to win for Marxism and Communism in China.” Also, The Freeman continued, “On his

own testimony, General Marshall supported our pro-Marxist China policy with his

eyes unblinkered with innocence.”

Thus, in the first half of 1950, our Far Eastern policy, made by Acheson and approved by

Truman and Dewey, was based on (1) the abandonment of Formosa to the expected

conquest by Chinese Communists, (2) giving no battle weapons to the Nationalist

Chinese or to the South Koreans, in spite of the fact that the Soviet was known

to be equipping the North Koreans with battle weapons and with military skills,

(3) the mere belief — at least, so stated — of our Secretary of State,

self-confessedly ignorant of the matter, that the Communists of China would

become angry with the Soviet. The sequel is outlined in section (d) below. -

Our second great mistake in foreign policy — unless votes in New York and other Northern cities are its motivation — was

our attitude toward the problem of Palestine. In the Eastern Mediterranean on the deck of the heavy cruiser, U.S.S. Quincy, which

was to bring him home from Yalta, President Roosevelt in February, 1945, received King Ibn Saud of Saudi Arabia.

According to General Elliott Roosevelt (As He Saw It, p. 245): “It had been Father’s hope that he would be able to

convince Ibn Saud of the equity of the settlement in Palestine of the tens of thousands of Jews driven from their European homes.”

But, as the ailing President later told Bernard Baruch, “of all the men he had talked to in his life, he had got least

satisfaction from this iron- willed Arab monarch.” General Roosevelt concludes thus: “Father ended by promising Ibn Saud that he

would sanction no American move hostile to the Arab people.” This may be considered the four-term President’s legacy on the subject,

for in less than two months death had completed its slow assault upon his frame and his faculties.

But the Palestine Problem, like the ghost in an Elizabethan drama, would not stay “down.” In the post-war years (1945 and after),

Jewish immigrants mostly from the Soviet Union or satellite states poured into the land once known as “Holy.”

These immigrants were largely Marxist in outlook and principally of Khazar antecedents. As the immigration progressed,

the situation between Moslems and this new type of Jew became tense.

The vote-conscious American politicians became interested. After many vacillations between “non-partition” which was recommended

by many American Jewish organizations and highly placed individual Jews, the United States — which has

many Zionist voters and few Arab voters — decided to sponsor the splitting of Palestine, which was predominantly Arab in population,

into Arab and Jewish zones. In spite of our lavish post-war tossing out of hundreds of millions and sometimes billions to almost

any nation — except a few pet “enemies” such as Spain — for almost any purpose, the United Nations was inclined to disregard our

sponsorship and reject the proposed new member. On Wednesday, November 26, 1947, our proposition received 25 votes out of 57

(13 against, 17 abstentions, 2 absent) and was defeated. Thus the votes had been taken and the issue seemed

settled. But, no!

Any reader who wishes fuller details should by all means consult the microfilmed New York

Times for November 26-30, and other pertinent periodicals, but here are the highlights:

The United Nations General Assembly postponed a vote on the partition of Palestine yesterday after Zionist supporters

found that they still lacked an assured two-thirds majority (article by Thomas J. Hamilton, New York Times, November 27,

1947).

Yesterday morning Dr. Aranha was notified by Siamese officials in Washington that the credentials of the Siamese delegation,

which had voted against partition in the Committee, had been canceled (November 27, 1947).

Since Saturday [November 22] the United States Delegation has been making personal contact with other delegates to obtain

votes for partition… The news from Haiti … would seem to indicate that some persuasion has now been brought to bear on

home governments … the result of today’s vote appeared to depend on what United

States representatives were doing in faraway capitals (from an article by Thomas

J. Hamilton, New York Times, November 28, 1947).

The result of our pro-"Israeli" pressures, denounced in some instances by representatives

of the governments who yielded, was a change of vote by nine nations: Belgium, France, Haiti, Liberia Luxemburg,

The Netherlands, New Zealand Paraguay, and the Philippines. Chile dropped — to “not voting” — from the pro-"Israeli"

twenty-five votes of November 26, and the net gain for U.S.-”Israeli” was 8. Greece

changed from “not voting” to “against,” replacing the dismissed Siamese

delegation and the “against” vote remained the same, 13, Thus the New York Times

on Sunday, November 30, carried the headline “ASSEMBLY VOTES PALESTINE

PARTITION; MARGIN IS 33-13; ARABS WALK OUT…. ”

The Zionist Jews of Palestine now had their seacoast and could deal with the Sovietized

Black Sea countries without further bother from the expiring British mandate.

The selection of immigrants of which over-populated “Israel” felt such great

need was to some extent, if not entirely, supervised by the countries of origin.

For instance, a high “Israeli” official visited Bucharest to coordinate with the

Communist dictator of Rumania, Ana Rabinsohn Pauker, the selection of immigrants

for “Israel.” “Soviet Bloc Lets Jews Leave Freely and Take Most Possessions to

Israel,” The New York Times headlined (November 26, 1948) a UP dispatch from

Prague.

The close ties between Communism and “Israel” were soon obvious to any penetrating reader

of the New York Times. A notable example is afforded in an article (March 12, 1948) by Alexander Feinberg entitled

“10,000 in Protest on Palestine Here: Throng Undaunted by Weather Mustered by Communist and Left-Wing Labor Leaders.”

Here is a brief quotation from this significant article:

Youthful and disciplined Communists raised their battle cry of “solidarity forever” as they

marched … The parade and rally were held under the auspices of the United

Committee to Save the Jewish State and the United Nations, formed recently after

the internationally minded Communists decided to “take over” an intensely

nationalistic cause, the partition of Palestine. The grand marshal of the parade

was Ben Gold, president of the Communist-led International Fur and Leather

Workers Union, CIO.

With the Jewish immigrants to Palestine came Russian and Czechoslovak (Skoda) arms. “Israel Leaning Toward Russia Its Armorer,”

the New York Herald-Tribune headlined on August 5, 1948. Here are quotations on the popularity of the Soviet

in “Israel” from Correspondent Kenneth Bilby’s wireless dispatch from Tel Aviv:

Russian prestige has soared enormously among all political factions … Certain Czech arms shipments which reached Israel

at critical junctures of the war, played a vital role in blunting the invasion’s five Arab armies … The Jews, who are certainly

realists, know that without Russia’s nod, these weapons would never have been available.

Mr. Bilby found that “the balance sheet” read “much in Russia’s favor” and found his conclusion "evidenced in

numerous ways — in editorials in the Hebrew press praising the Soviet Union" and also “in public pronouncements of political and

governmental leaders.” Mr. Bilby concluded also that the “political fact” of “Israeli” devotion to the Soviet might

“color the future of the Middle East” long after the issues of the day were settled. Parenthetically, the words of the

Herald-Tribune correspondent were prophetic. In its feature editorial of October 10, 1951, the Dallas Morning News commented

as follows on the announced determination of Egypt to seize the Sudan and the Suez Canal:

Beyond question, the Egyptian move is concerned with the understandable unrest stirred in the Arab world by the establishment

of the new State of Israel. The United Nations as a whole and Britain and the United States in particular did that. The

Moslem world could no more accept equably an effort to turn back the clock 2,000 years than would this country agree

to revert to the status quo of 1776.

Showing contempt, and her true colors, “Israel” voted with the Soviet Union and against the United States on the question

of admitting Communist China to the UN (broadcast of Lowell Thomas, CBS Network, November 13, 1951). Thus were we paid

for the immoral coercion by which we got “Israel” into the United Nations — a coercion which had given the whole world in

the first instance, a horrible but objective and above-board example of the Truman administration’s conception of elections!

But back to our chronology. In 1948, string with Soviet armor and basking in the sunshine of Soviet sympathy, “Israeli” troops

mostly born in Soviet-held lands killed many Arabs and drove out some 880,000 others, Christian and Moslem. These wretched

refugees apparently will long be a chief problem of the Arab League nations of the Middle East. Though most Americans are unaware,

these brutally treated people are an American problem also, for the Arabs blame their tragedy in large part on “the Americans —

for pouring money and political support to the Israelis; Harry Truman is the popular villain” (“The Forgotten Arab Refugees,”

by James Bell, Life, September 17, 1951). With such great sympathy for the Soviet Union, as shown above, it is not surprising

“Israel,” at once began to show features which are extremely leftist — to say the least For instance, on his return from

“Israel,” Dr. Frederick E. Reissig, executive director of the Washington (D.C.) Federation of Churches, “told of going to

many co-operative communities … Land for each ‘kibbutz’ — as such communities are called — is supplied by the government.

Everything — more or less — is shared by the residents” (Mary Jane Dempsey in Washington Times-Herald, April 24, 1951). For

fuller details, see “The Kibbutz” by John Hersey in The New Yorker of April 19, 1952.

After the “Israeli” seizure of the Arab lands in Palestine, there followed a long series of outrages including the bombings

of the British Officers’ Club in Jerusalem, the Acre Prison, the Arab Higher Command Headquarters in Jaffa, the Semiramis

Hotel, etc. These bombings were by “Jewish terrorists” (World Almanac, 1951). The climax of the brutality in “Israel” was the

murder of Count Bernadotte of Sweden, the United Nations mediator in Palestine! Here is the New York Times

story (Tel Aviv, September 18, 1948) by Julian Louis Meltzer:

Count Folke Bernadotte, United Nations Mediator for Palestine, and another United Nations official, detached from the

French Air Force, were assassinated this afternoon [September 17], within the Israeli-held area of Jerusalem.

Also, according to the New York Times, “Reuters quoted a Stern Group spokesman in Tel Aviv as having said, I am satisfied that

it has happened". A United Nations truce staff announcement confirmed the fact that Count Bernadotte had been

“killed by two Jewish irregulars,” who also killed the United Nations senior observer, Col. Andre Pierre Serot, of

the French Air Force.

Despite the fact that the murderers were Jews, and that the murdered UN officers were from countries worth no appreciable

political influence in the United States, American reaction to the murder of the United Nations mediator was by no means

favorable. It was an election year and Dewey droned on about “unity” while Truman trounced the “do-nothing Republican 80th Congress.”

For a month after the murders neither of them fished in the putrid pond of “Israeli”-dominated Palestine.

Strangely enough, it was Dewey who first threw in his little worm on a pinhook.

In a reply to a letter from the Constantinople-born Dean Alfange, Chairman of the Committee which founded the Liberal Party

of the State of New York, May 19, 1944 [Who's Who in America, Vol. 25, p. 44), Dewey wrote (October 22, 1948):

"As you know, I have always felt that the Jewish people are entitled to a homeland in Palestine which would be politically

and economically stable ... My position today is the same." On October 24 in a formal statement, Truman rebuked Dewey

for "injecting foreign affairs" into the campaign and — to change the figure of speech — raised the Republican candidate's

"six-spades" bid for Jewish votes by a resounding "ten-no-trumps":

So that everyone may be familiar with my position, I set out here the Democratic platform on Israel:

"President Truman, by granting immediate recognition to Israel, led the world in extending friendship and welcome to a people

who have long sought and justly deserve freedom and independence.

"We pledge full recognition to the State of Israel. We affirm our pride that the United States, under the leadership of

President Truman, played a leading role in the adoption of the resolution of Nov. 29, 1947, by the United Nations General

Assembly for the creation of a Jewish state.

"We approve the claim of the State of Israel to the boundaries set forth in the United Nations' resolution of Nov. 29 and

consider that modifications thereof should be made only if fully acceptable to the State of Israel.

"We look forward to the admission of the State of Israel to the United Nations and its full participation in the international

community of nations. We pledge appropriate aid to the State of Israel in developing its economy and resources.

"We favor the revision of the arms embargo to accord to the State of Israel the right of self-defense"

(New York Times, of Oct. 25, 1948).

But the President had not said enough. Warmed up, perhaps by audience contact, and flushed with the prospect of

victory, which was enhanced by a decision of the organized leftists to swing — after the opinion polls closed — from Wallace

to Truman, he swallowed the "Israel" cause, line, sinker and hook — the hook being never thereafter removed.

Here from the New York Times of Oct 29, 1948, is Warren Moscow's story:

President Truman made his strongest pro-Israel declaration last night. Speaking at Madison Square Garden to more

than 16,000 persons brought there under the auspices of the Liberal Party, the President ignored the Bernadotte Report and pledged

himself to see that the new State of Israel be "large enough, free enough, and strong enough to make its people self-supporting

and secure."

The President continued:

What we need now is to help the people of Israel and they've proved themselves in the best traditions of hardy pioneers.

They have created a modern and efficient state with the highest standards of Western civilization.

In view of the Zionist record of eliminating the Arab natives of Palestine, continuous bombings, and the murder of the

United Nations mediator, hardly cold in his grave, Mr. Truman owes the American people a documented exposition of his

conception of "best traditions" and "highest standards of Western civilization"

Indeed, our bi-partisan endorsement of Zionist aggression in Palestine — in bidding for the electoral vote of New York — is one

of the most reprehensible actions in world history.

The Soviet-supplied "Jewish" troops which seized Palestine had no rights ever before recognized in law or custom except

the right of triumphant tooth and claw (see "The Zionist Illusion," by Prof. W. T. Stace of Princeton University, Atlantic

Monthly, February, 1947).

In the first place the Khazar Zionists from Soviet Russia were not descended from the people of Hebrew religion in Palestine,

ancient or modern, and thus not being descended from Old Testament People (The Lost Tribes, by Allen H. Godfrey, Duke

University Press, Durham, N.C., 1930, pp. 257, 301, and passim), they have no Biblical claim to Palestine. Their claim

to the country rests solely on their ancestors' having adopted a form of the religion of a people who ruled there

eighteen hundred and more years before (Chapter II, above). This claim is thus exactly as valid as if the same or some other

horde should claim the United States in 3350 A.D. on the basis of having adopted the religion of the American

Indian! For another comparison, the 3,500,000 Catholics of China (Time, July 2, 1951) have as much right to the former Papal

states in Italy as these Judaized Khazars have to Palestine! (Bible students are referred to the Apocalypse, The

Revelation of St. John the Divine, Chapter II, Verse 9.)

Moreover, the statistics of both land-ownership and population stand heavily against Zionist pretensions. At the close

of the first World War, "there were about 55,000 Jews in Palestine, forming eight percent of the population... . Between

1922 and 1941, the Jewish population of Palestine increased by approximately 380,000, four-fifths of this being due to immigration.

This made the Jews 31 percent of the total population" (East and West of Suez, by John S. Badeau, Foreign Policy Association,

1943, p. 46). Even after hordes from Soviet and satellite lands had poured in, and when the United Nations was working on the

Palestine problem, the best available statistics showed non-Jews owning more land than Jews in all sixteen of the county-size

subdivisions of Palestine and outnumbering the Jews in population in fifteen of the sixteen subdivisions (UN

Presentations 574, and 573, November, 1947).

The anti-Communist Arab population of the world was understandably terrified by the arrival of Soviet-equipped troops in its

very center, Palestine, and was bitter at the presence among them — despite President Roosevelt's promise to Ibn Saud —

of Americans with military training. How many U.S. army personnel, reserve, retired, or on leave, secretly participated is not known.

Robert Conway, writing from Jerusalem on january 19, 1948, said: "More than 2,000 Americans are already

serving in Haganah, the Jewish Defense Army, highly placed diplomatic sources revealed today." Conway stated further that

a "survey convinced the Jewish agency that 5,000 Americans are determined to come to fight for the Jewish state

even if the U.S. government imposes loss of citizenship upon such volunteers." The expected number was 50,000 if no law on

forfeiting citizenship was passed by the U.S. Congress (N.Y . News cable in Washington Times-Herald, January 20, 1948).

Among Americans who cast their lot with "Israel" was David Marcus, a West Point graduate and World War II colonel.

Col. Marcus's service with the "Israeli" army was not revealed to the public until he was "killed fighting with Israeli forces

near Jerusalem" in June, 1948. At the dedication of a Brooklyn memorial to Colonel Marcus a "letter from President

Truman... extolled the heroic roles played by Colonel Marcus in two wars" (New York Times, Oct 11, 1948). At the

time of his death, Colonel Marcus was "Supreme commander of Israeli military forces on the Jerusalem front"

(AP dispatch, Washington Evening Star June 12, 1948).

The Arab vote in the united States is negligible — as the Zionist vote is not — and after the acceptance of "Israel" by the UN

the American government recognized as a sovereign state the new nation whose soil was fertilized by the blood of many

people of many nationalities from the lowly Arab peasant to the royal Swedish United Nations," mediator. "You can't shoot your

way into the United Nations, "said Warren Austin, U.S. Delegate to the UN, speaking of Communist China on

January 24, 1951 (Broadcasts of CBS and NBC). Mr. Austin must have been suffering from a lapse of memory, for that is

exactly what "Israel" did!

Though the vote of Arabs and other Moslem peoples is negligible in the United States, the

significance of these Moslem peoples is not negligible in the world (see the map

entitled "The Moslem Block" on p. 78 of Badeau' s East of Suez). Nor is their

influence negligible in the United Nations. The friendly attitude of the United

States toward Israel's bloody extension of her boundaries and other acts already

referred to was effectively analyzed on the radio (NBC Network, January 8, 1951)

by the distinguished philosopher and Christian (so stated by the introducer,

John McVane), Dr. Charles Malik, Lebanese Delegate to the United Nations and

Minister of Lebanon to the United States. Dr. Charles Malik of Lebanon is not to

be confused with Mr. Jacob (Jakkov, Yakop) Malik, Soviet Delegate with Andrei Y.

Vishinsky to the 1950 General Assembly of the United Nations (The United Nations

— Action for Peace, by Marie and Louis Zocca, Rutgers University Press, New

Brunswick, N. J., 1951). To his radio audience Dr. Malik of Lebanon spoke, in

part, as follows:

MR. MALIK: The United States has had a great history of very friendly relations with the Arab peoples

for about one hundred years now. That history has been built up by faithful missionaries, educators, explorers,

and archaeologists and businessmen for all these decades. Up to the moment when the Palestine problem began to be

an acute issue, the Arab peoples had a genuine and deep sense of love and admiration for the United States.

Then, when the problem of Palestine arose, with all that problem involved, by way of what we would regard as one-sided

partiality on the part of the United States with respect to Israel, the Arabs began to feel that the United States

was not as wonderful or as admirable as they had thought it was. The result has been that at the present moment there is

a real slump in the affection and admiration that the Arabs have had towards the United States. This slump has affected

all the relations between the United States and the Arab world, both diplomatic and non-diplomatic. And at the

present moment I can say, much to my regret, but it is a fact that throughout the Arab world, perhaps at no time in history

has the reputation of the United States suffered as much as it has at the present time. The Arabs, on the whole,

do not have sufficient confidence that the United States, in moments of crises, will not make decisions that will be prejudicial

to their interests. Not until the United States can prove in actual historical decision that it can withstand

certain inordinate pressures that are exercised on it from time to time and can really stand up for what one might

call elementary justice in certain matters, would the Arab people really feel that they can go back to their former attitude

of genuine respect and admiration for the United States.

Thus the mess of pottage of vote-garnering in New York and other doubtful states with large numbers of Khazar Zionists

has cost us the loyalty of twelve nations, our former friends, the so-called "Arab and Asiatic" block in the UN!

It appears also that the world's troubles from little blood-born "Israel" are not over. An official "Israeli" view of

Germany was expressed in Dallas, Texas, on March 18, 1951, when Abba S. Eban, ambassador of the state of "Israel" to the United

States and "Israel's" representative at the United Nations, stated that "Israel resents the rehabilitation of Germany."

Ambassador Eban visited the Texas city in the interest of raising funds for taking "200,000 immigrants this year,

600,000 within the next three years" (Dallas Morning News, March 13, 1951) to the small state of Palestine, or "Israel."

The same day that Ambassador Eban was talking in Dallas about "Israel's" resentment at the rehabilitation of Germany,

a Reuters dispatch of March 13, 1951 from Tel Aviv (Washington Times-Herald) stated that "notes delivered yesterday

[March 12] in Washington, London, and Paris and to the Soviet Minister at Tel Aviv urge the occupying powers of

Germany not to “hand over full powers to any German government” without express reservations for the payment of reparations

to “Israel” in the sum of $1,500,000,000.

This compensation was said to be for 6,000,000 Jews killed by Hitler. This figure has been used repeatedly

(as late as January, 1952 — “Israeli” broadcast heard by the author), but one who consults statistics and ponders the known facts of

recent history cannot do other than wonder how it is arrived at. According to Appendix VII, “Statistics on Religious Affiliation,”

of The Immigration and Naturalization Systems of the United States (A Report of the Committee on the

Judiciary of the United States Senate, 1950), the number of Jews in the world is 15,713,638.

The World Almanac, 1949, p. 289, is cited as the source of the statistical table reproduced on p. 842 of the government document.

The article in the World Almanac is headed “Religious Population of the World.” A corresponding item, with the title,

“Population, Worldwide, by Religious Beliefs” is found in the World Almanac for 1940 (p. 129), and in it the world

Jewish population is given as 15,319,359. If the World Almanac figures are correct, the world’ s Jewish population did

not decrease in the war decade, but showed a small increase.

Assuming, however, that the figures of the U.S. document and the World Almanac are in error, let us make an examination

of the known facts. In the first place, the number of Jews in Germany in 1939 was about 600,000 — by some estimates

considerably fewer — and of these, as shown elsewhere in this book, many came to the United States, some went to Palestine,

and some are still in Germany. As to the Jews in Eastern European lands temporarily overrun by Hitler’s troops, the

great majority retreated ahead of the German armies into Soviet Russia. Of these, many came later to the U.S., some moved

to Palestine, some unquestionably remained in Soviet Russia and may be a part of the Jewish force on the Iranian

frontier, and enough remained in Eastern Europe or have returned from Soviet Russia to form the hard core of the new

ruling bureaucracy in satellite countries (Chapter II). It is hard to see how all these migrations and all these

power accomplishments can have come about with a Jewish population much less than that which existed in Eastern Europe

before World War II. Thus the known facts on Jewish migration and Jewish power in Eastern Europe tend, like the

World Almanac figures accepted by the Senate Judiciary Committee, to raise a question as to where Hitler got the 6,000,000 Jews

he is said to have killed. This question should be settled once and for all before the United States backs

any “Israeli” claims against Germany. In this connection, it is well to recall also that the average German had no more

to do with Hitler’s policies than the average American had to do with Franklin Roosevelt’s policies; that 5,000,000

Germans are unaccounted for — 4,000,000 civilians (pp. 70, 71, above) and 1,000,000 soldiers who never returned from Soviet

labor camps (p. 137); and that a permanent hostile attitude toward Germany on our part is the highest hope of

the Communist masters of Russia.

In spite of its absurdity, however, the “Israeli” claim for reparations from a not yet created country, whose territory has

been nothing but an occupied land through the entire life of the state of “Israel,” may well delay reconciliation in

Western Europe; and the claim, even though assumed under duress by a West German government, would almost certainly be paid —

directly or indirectly — by the United States. The likelihood of our paying will be increased if a powerful

propaganda group puts on pressure in our advertiser- dominated press.

As to Ambassador Eban’s 600,000 more immigrants to “Israel”: Where will these people go — unless more Arab lands are taken

and more Christians and Moslems are driven from their homes?

And of equal significance: Whence will Ambassador Eban’s Jewish immigrants to “Israel” come? As stated above, a large portion

of pre-war Germany’s 600,000 Jews came, with other European Jews, to the United States on the return trips of vessels

which took American soldiers to Europe. Few of them will leave the United States, for statistics show that of all immigrants

to this country, the Jew is least likely to leave. The Jews now in West Germany will probably contribute few

immigrants to “Israel,” for these Jews enjoy a preferred status under U.S. protection. It thus appears that Ambassador

Eban’s 600,000 reinforcements to “Israel” — apart from stragglers from the Arab world and a possible mere handful

from elsewhere — can come only from Soviet and satellite lands. If so, they will come on permission of and by arrangement

with some Communist dictator (Chapter II, above). Can it be that many of the 600,000 will be young men with Soviet

military training? Can it be that such permission will be related to the Soviet’s great concentration of Jews in 1951

inside the Soviet borders adjacent to the Soviet- Iranian frontier?

Can it be true further that an army in Palestine, Soviet-supplied and Soviet-trained, will be one horn of a giant pincers

movement (“Keil und Kessel” was Hitler’s term) and that a thrust southward into oil-rich Iran will be the other? The astute

Soviet politicians know that the use of a substantial body of Jewish troops in such an operation might be relied on to prevent

any United States moves, diplomatic or otherwise, to save the Middle East and its oil from the Soviet. In fact, if spurred on

by a full-scale Zionist propaganda campaign in this country our State Department (pp. 232-233), following its precedent in regard

to “Israel,” might be expected to support the Soviet move.

To sum it up, it can only be said that there are intelligence indications that such a Soviet trap is being prepared.

The Soviet foreign office, however, has several plans for a given strategic area, and will activate the one that seems, in the

light of changing events, to promise most in realizing the general objective. Only time, then, can tell whether or not the Kremlin

will thrust with Jewish troops for the oil of Iran and Arabia.

Thus the Middle East flames — in Iran, on the “Israeli” frontier, and along the Suez Canal.

Could we put out the fires of revolt which are so likely to lead to a full scale third World War? A sound answer was given by

The Freeman (August 13, 1950), which stated that “all we need to do to insure the friendship of the Arab and Moslem

peoples is to revert to our traditional American attitudes toward peoples who, like ourselves, love freedom.” This is true

because the “Moslem faith is founded partly upon the teachings of Christ.” Also, “Anti-Arab Policies Are Un-American

Policies,” says William Ernest Hocking in The Christian Century (“Is Israel A ‘Natural Ally’?” September 19, 1951).

Will we work for peace and justice in the Middle East and thus try to avoid World War III ? Under our leftist-infested State

Department, the chance seems about the same as the chance of the Moslem voting population and financial power

surpassing those of the Zionists during the next few years in the State of New York!

The Truman administration’s third great mistake in foreign policy is found in its treatment of defeated Germany.

In China and Palestine, Mr. Truman’s State Department and Executive Staff henchmen can be directly charged with sabotaging

the future of the United States; for despite the surrender at Yalta the American position in those areas was still far from hopeless

when Roosevelt died in April, 1945. With regard to Germany, however, things were already about as bad as possible, and

the Truman administration is to be blamed not for creating but for tolerating and continuing a situation dangerous to the future

security of the United States.

At Yalta the dying Roosevelt, with Hiss at his elbow and General Marshall in attendance, had consented to the brutality of letting

the Soviet use millions of prisoners of war as slave laborers — one million of them still slaves or dead before their time.

We not only thus agreed to the revival of human slavery in a form far crueler than ever seen in the Western world; we also practiced

the inhumanity of returning to the Soviet for Soviet punishment those Western-minded Russian soldiers who sought sanctuary in

areas held by the troops of the once Christian West! The Morgenthau plan for reviving human slavery by its provision for

“forced labor outside Germany” after the war (William Henry Chamberlin, America’s Second Crusade, Henry Regnery Company,

Chicago, 1950, p. 210) was the basic document for these monstrous decisions. It seems that Roosevelt initialed

this plan at Quebec without fully knowing what he was doing (Memoirs of Cordell Hull, Vol. II) and might have modified some of the

more cruel provisions if he had lived and regained his strength. Instead, he drifted into the twilight, and at Yalta Hiss and Marshall

were in attendance upon him, while Assistant Secretary of State Acheson was busy in Washington.

After Roosevelt’s death the same officials of sub-cabinet rank or high non-cabinet rank carried on their old policies and worked

sedulously to foment more than the normal amount of post-war unrest in Western Germany. Still neglected was the sound strategic maxim

that a war is fought to bring a defeated nation into the victor’s orbit as a friend and ally. Indeed, with a much narrower world horizon

than his predecessor, Mr. Truman was more easily put upon by the alien-minded officials around him. To all intents and purposes,

he was soon their captive.

From the point of view of the future relations of both Germans and Jews and of our own national interest, we made a grave mistake

in using so many Jews in the administration of Germany. Since Jews were assumed not to have any “Nazi contamination,”

the “Jews who remained in Germany after the Nazi regime were available for use by military government”

(Zink: American Military Government in Germany, p. 136). Also, many Jews who had come from Germany to this country

during the war were sent back to Germany as American officials of rank and power. Some of these individuals were actually

given on-the-spot commissions as officers in the Army of the United States. Unfortunately, not all refugee Jews

were of admirable character. Some had been in trouble in Germany for grave non-political offenses and their repatriation in the dress

of United States officials was a shock to the German people. There are testimonies of falsifications by Jewish interpreters and

of acts of vengeance. The extent of such practices is not here estimated, but in any case the employment of such

large numbers of Jews — whether of good report, or bad — was taken by Germans as proof of Hitler’s contention

(heard by many Americans as a shortwave song) that America is a “Jewish land,” and made rougher our road toward reconciliation and

peace.

A major indelible blot was thrown on the American shield by the Nuremberg war trials in which, in clear violation of the spirit

of our own Constitution, we tried people under ex post facto laws for actions performed in carrying out the orders of

their superiors. Such a travesty of justice could have no other result than teaching the Germans — as the Palestine matter taught

the Arabs — that our government had no sense of justice. The persisting bitterness from this foul fiasco is seen in the popular quip

in Germany to the effect that in the third World War England will furnish the navy, France the foot soldiers, America the

airplanes, and Germany the war-criminals.

In addition to lacking the solid foundation of legal precedent our “war trials” afforded a classic example of the “law’s delay.”

Seven German soldiers, ranging in rank from sergeant to general, were executed as late as June 7, 1951. Whatever these men and

those executed before them may or may not have done, the long delay had two obvious results — five years of jobs for the

U.S. bureaucrats involved and a continuing irritation of the German people — an irritation desired by Zionists and Communists

The Germans had been thoroughly alarmed and aroused against Communism and used the phrase “Gegen Welt Bolshewismus”

(“Against World Communism”) on placards and parade banners while Franklin Roosevelt was courting it (“We need those votes”).

Consequently the appointment of John J. McCloy as High Commissioner (July 2, 1949) appeared as an affront, for this man was

Assistant Secretary of War at the time of the implementation of the executive order which abolishes rules designed

to prevent the admission of Communists to the War Department; and also, before a Congressional Committee appointed to

investigate Communism in the War Department, he testified that Communism was not a decisive factor in granting or

withholding an army commission. Not only McCloy’s record (Chapter VIII, c) but his manner in dealing with the Germans

tended to encourage a permanent hostility toward America. Thus, as late as 1950, he was still issuing orders to them not

merely plainly but “bluntly” and “sharply” (Drew Middleton in the New York Times, Feb, 7, 1950).

Volumes could not record all our follies in such matters as dismantling German plants for the Soviet Union while spending nearly

a billion a year to supply food and other essentials to the German people, who could have supported themselves by work in the destroyed

plants. For details on results from dismantling a few chemical plants in the Ruhr, see “On the Record” by Dorothy Thompson, Washington

Evening Star, June 14, 1949. The crowning failure of our policy, however, came in 1950. This is no place for a full discussion

of our attitude toward the effort of 510,000 Jews — supported, of course, from the outside as shown in Chapter IV, above — to ride

herd on 62,000,000 Germans (1933, the figures were respectively about 600,000 and 69,000,000 by 1939) or the ghastly sequels. It

appeared as sheer deception, however, to give the impression, as Mr. Acheson did, that we were doing what we could to secure the

cooperation of Western Germany, when Mr. Milton Katz was at the time (his resignation was effective August 19, 1951) our overall

Ambassador in Europe and, under the far from vigorous Marshall, the two top assistant secretaries of Defense were the Eastern

European Jewess, Mrs. Anna Rosenberg, and Mr. Marx Leva! Nothing is said or implied by the author against Mr. Katz, Mrs. Rosenberg

or Mr. Marx Leva, or others such as Mr. Max Lowinthal and Mr. Benjamin J. Brttenwieser, who have been prominent figures in our recent

dealings with Germany, the former as Assistant to Commissioner McCloy and the latter as Assistant High Commissioner of the

United States. As far as the author knows, all five of these officials are true to their convictions. The sole point here stressed

is the unsound policy of sending unwelcome people to a land whose good will we are seeking — or perhaps

only pretending to seek.

According to Forster’s A Measure of Freedom (p. 86), there is a “steady growth of pro-German sentiment in the super-Patriotic press” in the United States. The

context suggests that Mr. Forster is referring in derision to certain pro-American sheets of small circulation, most of which do not carry

advertising. These English-language papers with their strategically sound viewpoints can, however, have no appreciable circulation

in Germany, if any at all, and Germans are forced to judge America by its actions and its personnel. In both, we have moved for the

most part rather to repel them than to draw them into our orbit as friends.

If we really wish friendship and peace with the German people, and really want them on our side in case of another world-wide war,

our choice of General Eisenhower as Commander-in-chief in Europe was most unfortunate. He is a tactful, genial man,

but to the Germans he remains — now and in history — as the Commander who directed the destruction of their cities with civilian

casualties running as high as a claimed 40,000 in a single night, and directed the U.S. retreat from the out-skirts of Berlin.

This retreat was both an affront to our victorious soldiers and a tragedy for Germany, because of the millions of additional people

it placed under the Soviet yoke, and because of the submarine construction plants, guided missile works, and other factories it

presented to the Soviet Moreover, General Eisenhower was Supreme Commander in Germany during the hideous atrocities perpetrated

upon the German people by displaced persons after the surrender (Chapter IV, above). There is testimony to General Eisenhower’s lack

of satisfaction with conditions in Germany in 1945, but he made — as far as the author knows — no strong gesture such as securing

his assignment to another post. Finally, according to Mr. Henry Morgenthau (New York Post, November 24, 1947), as quoted in

Human Events and in W. H. Chamberlin’s America’s Second Crusade, General Eisenhower said: “The whole German population

is a synthetic paranoid” and added that the best cure would be to let them stew in their own juice. All in all, sending

General Eisenhower to persuade the West Germans to “let bygones by bygones” (CBS, January 20, 1951), even before the signing of a

treaty of peace, was very much as if President Grant had sent General Sherman to Georgia to placate the Georgians five years

after the burning of Atlanta and the march to the sea — except that the personable Eisenhower had the additional initial handicap

of Mr. Katz breathing on his neck, and Mrs. Anna Rosenberg in high place in the Department of Defense in Washington !

The handicap may well be insurmountable, for many Germans, whether rightly or not, believe Jews are responsible for all their woes.

Thus, after the Eisenhower appointment, parading Germans took to writing on their placards not their old motto “Gegen Welt

Bolshewismus” but “Ohne mich” (AP despatch from Frankfurt-am-Main, Germany, February 4, 1951) which may be translated “Leave me out.”

In this Germany, whose deep war wounds were kept constantly festering by our policy, our government has stationed some six divisions

of American troops. Why? In answering the question remember that Soviet Russia is next door, while our troops, supplies, and

reinforcements have to cross the Atlantic! Moreover, if the Germans, fighting from and for their own homeland, “failed with a

magnificent army of 240 combat divisions” (ex-President Herbert Hoover, broadcast on “Our National Policies on

This Crisis,” Dec. 20, 1950) to defeat Soviet Russia, what do we expect to accomplish with six divisions ? Of course,

in World War II many of Germany’s divisions were used on her west front and America gave the Soviet eleven billion dollars

worth of war materiel; still by any comparison with the number of German divisions used against Stalin, six is a

very small number for any military purpose envisioning victory. Can it be that the six divisions have been offered by some

State Department schemer as World War Ill’s European parallels to the “sitting ducks” at Pearl Harbor and the

cockle shells in Philippine waters? (See Chapter VII, d, below and Design for War, by Frederick R. Sanborn, The Devin-Adair Company,

New York, 1951).

According to the military historian and critic, Major Hoffman Nickerson, our leaders have some “undisclosed purpose of their own,

if they foresee war they intend that war to begin either with a disaster or a helter-skelter retreat”

(The Freeman, July 2, 1951). In any case the Soviet Union — whether from adverse internal conditions, restive satellites,

fear of our atomic bomb stockpile, confidence in the achievement of its objectives through diplomacy and

infiltration, or other reasons — has not struck violently at our first bait of six divisions. But, under our provocation

the Soviet has quietly got busy.

For five years after the close of World War II, we maintained in Germany two divisions and the Soviet leaders made little

or no attempt to prepare the East German transportation network for possible war traffic (U.S. News and World Report,

January 24, 1951). Rising, however, to the challenge of our four additional divisions (1951), the Soviet took positive action.

Here is the story (AP dispatch from Berlin in Washington Times-Herald, April 30, 1951):

Russian engineers have started rebuilding the strategic rail and road system from Germany’s Elbe River,

East German sources disclosed today. The main rail lines linking East Germany and Poland with Russia are being

double-tracked, the sources said. The engineers are rebuilding Germany’s highway and bridge network to support tanks

and other heavy artillery vehicles.

The Soviet got busy not only in transportation but in personnel and equipment According to Drew Middleton

(New York Times, August 17, 1951), “All twenty-six divisions of the Soviet group of armies in Eastern Germany are being brought

to full strength for the first time since 1946.” Also, a “stream of newly produced tanks, guns, trucks, and light weapons is flowing

to divisional and army bases.” There were reports also if the strengthening of satellite armies.

These strategic moves followed our blatantly announced plans to increase our forces in Germany. Moreover, according to Woodrow Wyatt,

British Undersecretary for War, the Soviet Union had “under arms” in the summer of 1951 “215 divisions and more

than 4,000,000 men” (AP dispatch in New York Times, July 16, 1951). Can it be possible that our State Department is seeking

ground conflict with this vast force not only on their frontier but on the particular frontier which is closest

to their factories and to their most productive farm lands?

In summary, the situation of our troops in Germany is part of a complex world picture which is being changed daily

by new world situations such as our long delayed accord with Spain and a relaxing of the terms of our treaty with Italy.

There are several unsolved factors. One of them is our dependence — at least in large part — on the French transportation

network which is in daily jeopardy of paralysis by the Communists, who are numerically the strongest political party

in France. Another is the nature of the peace treaty which will some day be ratified by the government of West Germany

and the Senate of the United States — and thereafter the manner of implementing that treaty.

As we leave the subject, it can only be said that the situation of our troops in Germany is

precarious and that the question of our relations with Germany demands the

thought of the ablest and most patriotic people in America — a type not overly

prominent in the higher echelons of our Department of State in recent years. Having by three colossal “mistakes” set the stage for possible disaster in the Far East,

in the Middle East, and in Germany, we awaited the enemy’s blow which could be

expected to topple us to defeat. It came in the Far East.

As at Pearl Harbor, the attack came on a Sunday morning — June 2, 1950. On that day North Korean Communist troops crossed

the 38th parallel from the Soviet Zone to the recently abandoned U.S. Zone in Korea and moved rapidly to the South. Our

government knew from several sources about these Communist troops before we moved our troops out on January 1, 1949, leaving

the South Koreans to their fate. For instance, in March, 1947, Lieutenant General John R. Hodge, U.S. Commander in Korea,

stated “that Chinese Communist troops were participating in the training of a Korean army of 500,000 in Russian-held North Korea”

{The China Story, p. 51).

Despite our knowledge of the armed might of the forces in North Korea; despite our vaunted failure to arm our former wards,

the South Koreans; despite our “hands off” statements placing Formosa and Korea outside our defense perimeter and generally

giving Communists the green light in the Far East; and despite President Truman’s statement as late as May 4, 1950, that there

would be "no shooting war" we threw United States troops from Japan into that unhappy peninsula — without the authority of

Congress — to meet the Communist invasion.

Our troops from Japan had been trained for police duty rather than as combat units and were “without the proper weapons”

(P.L. Franklin in National Republic, January, 1951). This deplorable fact was confirmed officially by former Defense

Secretary, Louis Johnson, who testified that our troops in Korea “were not equipped with the things that you would need

if you were to fight a hostile enemy. They were staffed and equipped for occupation, not for war or an offensive”

(testimony before combined Armed Services and Foreign Relations Committees of the Senate, June, 1951, as quoted by U.S. News and

World Report, June 22, 1951, pp. 21-22). Our administration had seen to it also that those troops which became our South Korean allies

were also virtually unarmed, for the Defense Department “had no establishment for Korea. It was under the State

Department at that time” (Secretary Johnson’s testimony) .

Under such circumstances, can any objective thinker avoid the conclusion that the manipulators of United States policy

confidently anticipated the defeat and destruction of our forces, which Secretary Acheson advised President Truman to

commit to Korea in June, 1950?

But the leftist manipulators of the State Department whether in that department or on the outside — were soon confronted by a miracle

they had not foreseen. The halting of the North Korean Communists by a handful of men under such handicaps was one of the remarkable

and heroic pages in history credit for which must be shared by our brave front-line fighting men; their field commanders including

Major General William F. Dean, who was captured by the enemy, and Lieutenant General Walton H. Walker, who died in Korea;

and their Commander-in-Chief, General of the Army Douglas MacArthur.

The free world applauded what seemed to be a sudden reversal of our long policy of surrender to Soviet force in the Far East,

and the United Nations gave its endorsement to our administration’s venture in Korea. But the same free world was stunned when

it realized the significance of our President’s order to the U.S. Seventh Fleet to take battle station between Formosa and the Chinese

mainland and stop Chiang from harassing the mainland Communists. Prior to the Communist aggression in Korea, Chiang was dropping